Free shipping in Portugal and Spain on orders over € 50 amount

Italian Renaissance

Artbooks Italian Renaissance

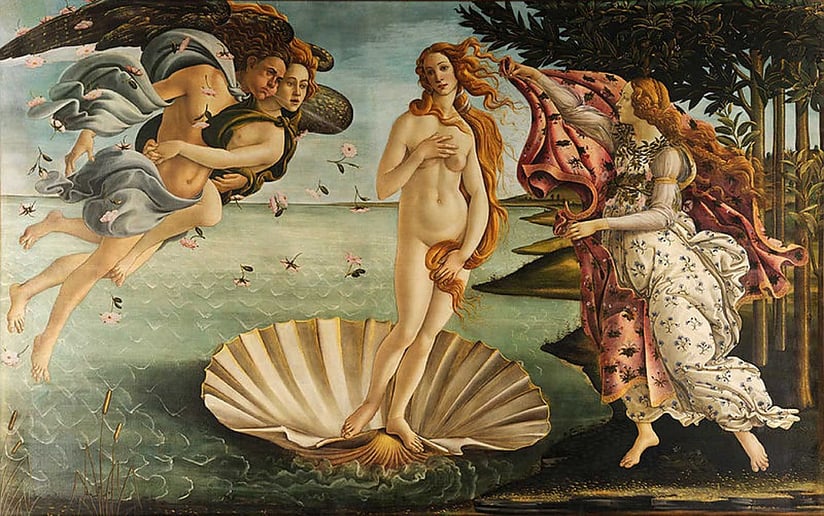

Many art books are published about the Italian Renaissance. Famous painters of that period are still highly appreciated in our days. Best known is probably Leonardo da Vinci, for which we have created a specific category. Another big name is Sandro Botticelli, especially for his world-famous painting The Birth of Venus, which can be admired in the Uffizi Museum in Florence. At this page and following pages you will find books of art about the Renaissance period, its painting, sculpture and architecture, published by well known artbook publishers, such as Oxford University Press, Princeton University Press, Running Press, Silvana Editoriale, Skira and Taschen. Enjoy!

Sandro Botticelli (1445-1510), The Birth of Venus, c. 1484-1486,

tempera on canvas, 173 x 279 cm, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence

The Renaissance style period covers a long period within art history. It greatly influenced developments in painting, sculpture and architecture of the Western world. The Renaissance in visual art is also intertwined with major social, religious and political changes in Italy and northern Europe.

The literal translation of the word renaissance is ‘renewed flowering’ or ‘rebirth’. The name echoes the need for a new view of the world. The time had come in the late Middle Ages for a new way of thinking about science and art forms. During this period, around 1400, Renaissance art begins to emerge. A century later, Renaissance style blossomed briefly during the High Renaissance (around 1500-1520). That flourishing phase of the Renaissance turns into the style of Mannerism. In some versions of art history, Mannerism is included in the Renaissance in other versions it is not. Either way around 1600, the style period of mannerism comes to an end. It marks the beginning of the Baroque style period.

Renaissance

by Art Historian Sander Kletter

Delineating Renaissance

Revaluation for Homer and Plato

A major force behind the new way of thinking at the end of the Middle Ages, which ushered in the Renaissance, was the rise of humanism. Important are the studies of the Italian scholar Francesco Petrarch (1304-1374). He wanted to spread the Greek language in Europe, bringing writers and philosophers such as Homer and Plato back to prominence. Because there was no attention to the Greek language in the Middle Ages, Homer and Plato had been silenced in his view. The humanists focused on the culture of classical antiquity as an alternative to the Christian religious teachings of the Middle Ages. Because of Petrarch's advocacy, interest in Greek and Latin culture, philosophy and language spread extraordinarily fast during the Renaissance. The humanists felt that the imagery used in antiquity by the Greeks and Romans should become the new ideal to be pursued. The culture of ancient civilisation was the touchstone by which to live. The expression rebirth, therefore, lies mainly in the revaluation of classical antiquity. An example of this renewed interest in classical antiquity is Sandro Botticelli's painting The Birth of Venus (c. 1484-1486, see first image above this article). In this iconic painting, the artist gives shape to the ideals of beauty of classical antiquity. In sculpture, the first steps were taken in the early Renaissance following the example of classical antiquity by Donatello (c. 1386-1466) in Florence.

Piero della Francesca (1420-1492), The Flaggelation of Christ, 1455-1460, oil and tempera on panel, 58.4 x 81.5 cm, Galleria delle Marche, Urbino

In the work of the Italian painter Giotto (1276-1337), characteristics can already be detected that correspond to later Renaissance stylistic features. He no longer applied the gold background as he had learned from his teacher Cimabue (c. 1240-1302). Gold formed the standard background of every painting in the Middle Ages. Instead, Giotto paints a landscape, interior or part of architecture on the background of a Christian main scene. The artist thus suddenly emphatically claims a place for humans in creation. He can be seen as an early Renaissance artist. He was active well before the Renaissance would define the face of art. The focus of the early Renaissance was in Florence, the very place where Giotto realised several major works.

The talented master builder Filippo Brunelleschi (1377-1446) became famous for his buildings in which he revived the ancient style. Very important for further development in the Renaissance, and for painting in particular, was his invention of linear perspective. It was Brunelleschi who first saw that the painting can be seen as a window. A window through which the viewer looks at the depicted reality. This insight led him to invent viewing lines, the so-called ‘orthogonals’. These are the perspective lines, which are perpendicular to the painting plane. The basic principle of perspective is that parallel lines in reality run to the same vanishing point on the horizon.

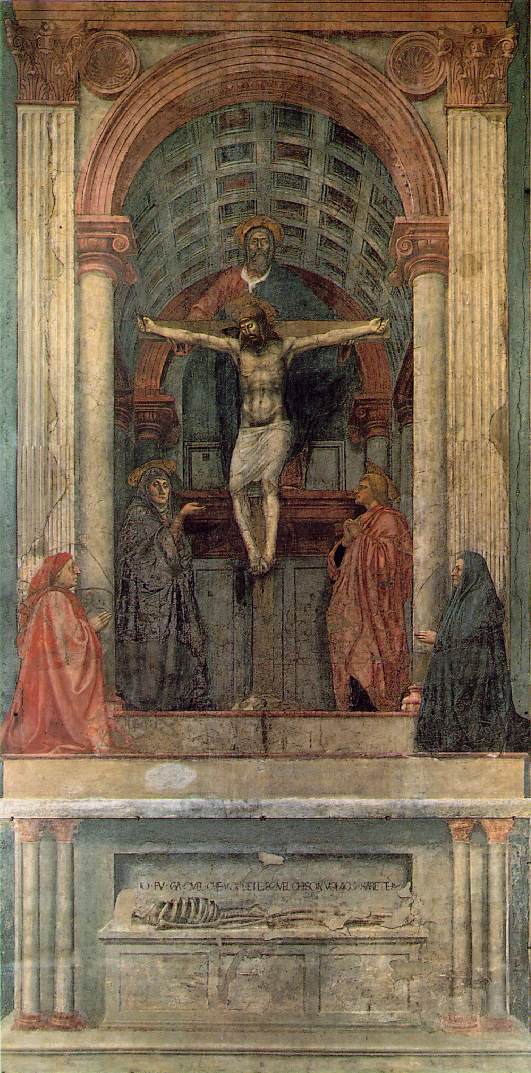

Many artists made grateful use of Brunelleshi's revolutionary invention. The early Renaissance painter Masaccio (1401-1428) did this in particular. He created the fresco The Holy Trinity (c. 1425-1427, see image above), which shows a niche in which a familiar Christian scene takes place. We see Christ hanging on the cross. In front of the niche are two human figures kneeling, the donors who gave the artwork to the church. Thanks to the application of the perspective system, he manages to convincingly place the figures in a spatial context. The niche seems to have real depth. One had not seen such an illusionistic image before. The astonishment of the Florentine public was therefore great. Another example of an early Renaissance artist who applied perspective was Piero della Francesca (1420-1492). See the second image of his article, his painting The Flaggelation of Christ (1455-1460), in which he used the method of linear perspective by Brunelleschi. When an artist works with perspective lines, he can convincingly suggest depth and space in the suggested architectural elements within his paintings.

Brunelleschi and the linear perspective

Masaccio (1401-1428), The Holy Trinity, With Maria, Saint John and Donors, c. 1425-1427, fresco, 667 x 317 cm, Santa Maria Novella, Florence

Leonardo da Vinci and the High Renaissance

The classical ideal sought by Renaissance artists was only really achieved at the time of the High Renaissance, between 1500 and 1520. Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519), Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475-1564) and Raphael (1483-1520) are considered the most important masters of this period. They also act as examples of the all-knowing scholar, the ‘Uomo universale’. Indeed, they were not only artists, but also, for instance, inventors, writers, philosophers, scientists, architects and engineers. The scientific approach to nature characterises the transition to the High Renaissance. Leonardo da Vinci is said to have visited several places in southern Italy. There, he became enchanted by the overwhelming mystery of nature's whimsical forms, such as the volcano Etna, raging seas and dark caves. Through thorough study of nature, the interpretation of the precepts of classical tradition changed. There was more room for the artist's personal findings.

Typical of Leonardo's style is the use of ‘sfumato’, the gradual blurring of contours through the superimposition of several transparent layers of colour. An example of sfumato can be found in his painting Virgin of the Rocks (c. 1483-1494, see image above). The mysterious atmosphere in his paintings is intensified by the application of a distinctive chiaroscuro technique, which had been used earlier by Masaccio. This involves greatly exaggerating light-dark contrasts. In 1500, Leonardo left for Venice, where he befriended the artist Giorgione (1478-1510), a pupil of Giovanni Bellini (c.1430-1516). Leonardo's painting techniques really appealed to Giorgione. He also started using them in his paintings. Giorgione, in turn, would be a great influence on Titian (c.1488/1490-1576), who enriched Venetian painting for his use of bright colours. The style and idealised figures typical of the High Renaissance were greatly exaggerated during Mannerism, which followed the High Renaissance as a style period. Artist Paolo Veronese's (1528-1588) work has traits of both the High Renaissance and Mannerism.

Leonardo da Vinci, Virgin of the Rocks, c. 1483-1494,

oil on panel, 199 x 122 cm, Louvre, Paris

Giorgione (c. 1478-1510), The Tempest, c. 1507-1508, oil on canvas, 82 x 73 cm, Galleria dell'Accademia, Venice

In Northern Europe, the Renaissance style was used by important artists such as Lucas Cranach the Elder, Albrecht Dürer and Hans Holbein the Younger. From the latter his The Ambassadors (1533) and Portrait of Jane Seymour c. 1536-1537) are famous Renaissance masterpieces.

In the Low Countries, in cities such as Ghent and Bruges, some painters were active at the time of the High Renaissance who are considered both ‘Northern Renaissance’ and ‘Late Gothic’. They are also called Flemish Primitives. Rogier van der Weyden, Hugo van der Goes, Jan van Eyck, Petrus Christus and Hans Memling are the most famous.

In France there was Jean Fouquet, painter at the royal court, who personally visited Italy in 1437. His works are influenced by the Florentine Renaissance painters.

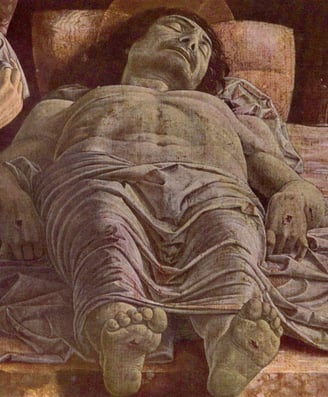

Notable Italian Renaissance artists not previously mentioned on this page include: Fra Angelico, Sofonisba Anguissola, Jacopo Bassano, Vittore Carpaccio, Andrea del Castagno, Cima da Conegliano, Piero di Cosimo, Lorenzo di Credi, Carlo Crivelli, Dosso Dossi, Domenico Ghirlandaio, Lorenzo Lotto, Andrea Mantegna, Antonello da Messina, Pietro Perugino, Sebastiano del Piombo, Pisanello, Andrea del Sarto, Luca Signorelli, Paolo Uccello, Andrea del Verrocchio, Giorgio Vasari and Antonio Vivarini. Well-known Italian mannerists include: Alessandro Allori, Arcimboldo, Angelo Bronzino, Antonio da Correggio, theorist Giovanni Paolo Lomazzo, Parmigianino, Jacopo da Pontormo, Giulio Romano, Tintoretto and the already mentioned Paolo Veronese.

Sander Kletter, March 8, 2025

More renaissance artists

Andrea Mantegna (c.1431-1506), The Lamentation over the Dead Christ, c.1475-1478,

oils on panel, 66 x 81 cm, Kenwood House, Hampstead, London

© Sander Kletter/Alexanders Artbooks 2025